If you care to understand how the “energy part” of our economy feeds back and shapes the “non-energy part” of the economy, then this blog’s for you!

Essentially every energy analyst and energy economist should understand the results of this paper.

The findings of this paper have important implications for economic modeling in that the paper helps explain how fundamental shifts in resources costs relate to economic structure and economic growth.

This is a summary of a my publication in Biophysical Economics and Resource Quality:

King, Carey W. Information Theory to Assess Relations Between Energy and Structure of the U.S. Economy Over Time. Biophysical Economics and Resource Quality, 2016, 1 (2), 10. doi: 10.1007/s41247-016-0011-y. View paper free online here: link, or download a pre-print draft: ![]() link.

link.

One of the major driving influences of the research behind this paper comes from a mixture of ideas from Charlie Hall and Joseph Tainter. Hall (an ecologist by degree) is seen by many as “Dr. EROI” where EROI = ‘energy return on energy invested’ is the most-common ‘net energy’ term for a calculation for how much energy you get for each unit of energy you use to extract energy. Tainter (an anthropologist) appreciates the concept of net energy and has applied it qualitatively to describe that more net energy and gross energy is required to enable the structure of ‘complex’ societies (mostly, but not entirely, in a pre-industrial context):

“Energy gain has implications beyond mere accounting. It fundamentally influences the structure and organization of living systems, including human societies.”

(Tainter et al, 2003: article link)

WHY DO WE CARE? Complexity … redundancy versus efficiency … equality versus hierarchy …

The reason why we care to understand the state of the economy, or other complex systems, in terms of efficiency and redundancy (or resilience) is that more efficient systems (that produce more output for increasingly fewer inputs) are also brittle. If conditions change, they are less able to adapt. The same conditions that allowed them to greatly increase output with fewer inputs also force them to greatly decrease output when those fewer inputs are no longer available (e.g., oil imports are embargoed).

In this paper, I put Tainter and other ideas relating to tradeoffs of “efficiency” and “redundancy” to the test. I did so using the concepts of ecologist Robert Ulanowicz, who has for a large part of his career worked on calculating the ‘structure’ of ecosystems using an information theory approach. I was immediately convinced that Ulanowicz’s framework could be applied to economic data to test Tainter’s concept and also test if there indeed was any relationship we could see between net energy and the economy.

Thus, my paper describes the changing structure of the United States’ (U.S.) domestic economy by applying Ulanowicz’s information theory-based metrics (with some added twists I felt necessary to be more precise) to the U.S. input-output (I-O) tables (e.g., economic transactions) from 1947 to 2012. The findings of this paper have important implications for economic modeling in that the paper helps explain how fundamental shifts in resources costs relate to economic structure and economic growth.

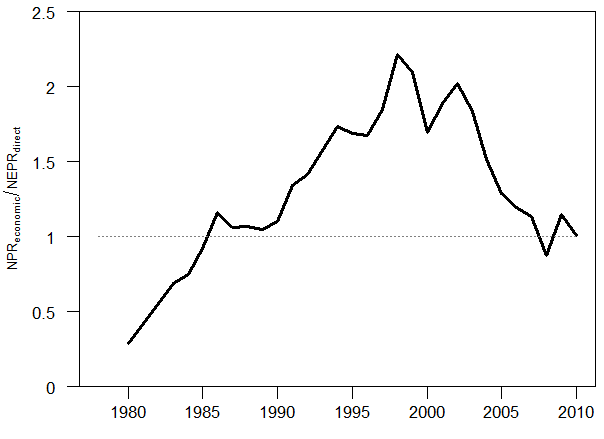

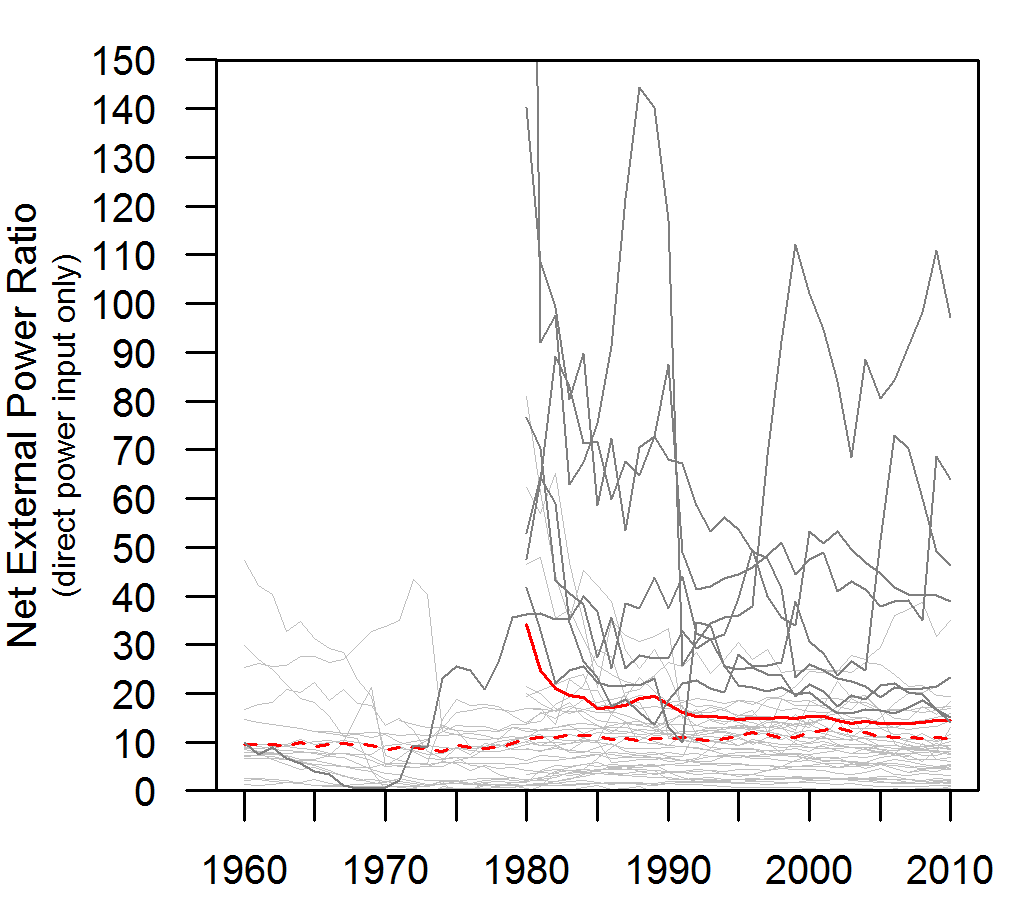

The results of this paper (summarized in Figure 1) show that increasing gross power consumption, as well as a less spending by food and energy sectors, correlate to increased distribution of money among economic sectors, and vice versa.

In short, the ideas of Hall and Tainter appear to be true: the U.S. economic structure does change significantly depending upon (1) the rate at which we consume energy (e.g., power as energy/year) and (2) the relative cost of energy (and food)!!

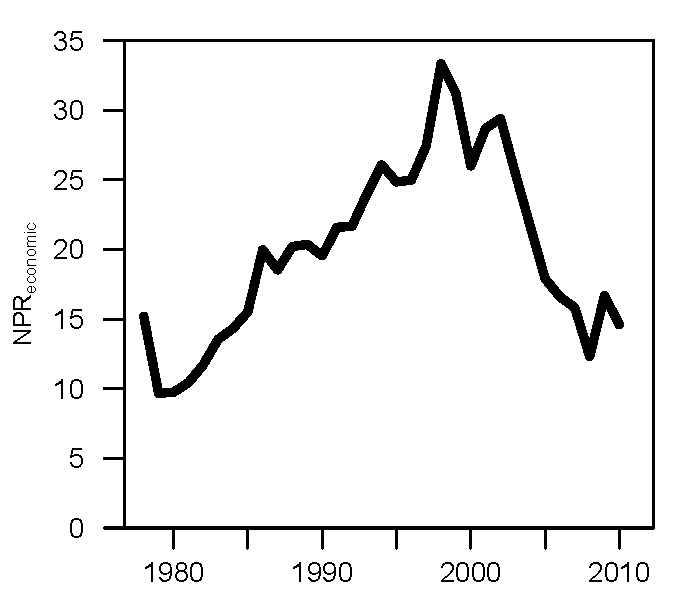

I will now explain in more detail how to understand the results in Figure 1 (see Appendix at the end of this blog to understand how the calculations work). In Figure 1, the “Net Power Ratio” (NPR) is a metric of “energy and food gain” that is larger when energy and food costs are lower. Its definition is: NPR = (Gross Domestic Product) / (Expenditures of Energy and Food sectors).

Figure 1. After 2002, when energy, food, and water sector costs increased after reaching their low point, the direction of structural change of the U.S. economy reversed trends indicating that money became increasingly concentrated in fewer types of transactions.

The information theory metrics indicate two time periods at which major structural shifts occurred: The first was between 1967 and 1972, and the second was around the turn of the 21st Century when food and energy expenditures no longer continued to decrease after 2002.

Structural Shift 1 (1967 or 1972):

The change in trend around 1967 (could possibly be described as 1972) is that equality shifts from increasing to decreasing.

From 1945 until 1967/1972, both equality and redundancy were increasing. The U.S. was increasing its power consumption (e.g., energy/yr) at about 4%/yr. That is to say, the U.S. economy was booming after World War II gobbling up more and more energy every year at a high rate because energy (e.g., oil) was abundant and getting cheaper by the day.

Increasing equality means that over time each sector of the economy was coming closer to the condition that each sector had approximately the same total sales in a year. That is to say, the sales of the “construction” sector were becoming more equal to the sales of the “aircraft and parts” and “amusement” sectors. Some sectors would sell less over time (e.g., “farming”) and some sectors would sell more (e.g., “metals manufacturing”). This makes sense because some “new” sectors have practically no transactions in 1954 whereas they are more integrated into the economy in 1967 (e.g, “aircraft and parts” and “amusement”).

Increasing redundancy means that over time each sectoral transaction (e.g., “farms” to “metals manufacturing” or “oil and gas” to “machinery and equipment manufacturing”) was becoming more equal. This again makes sense because some “new” sectors have practically no transactions in 1954 whereas they are more integrated into the economy in 1967.

The structural shift in the U.S. economy can be explained by a few things that came to a head in the late 1960s and early 1970s:

- U.S. had little global competition for resources in immediate aftermath of World War II (e.g., Europe and Japan were devastated and needed time to recover).

- Oil: Peak U.S. crude oil production in 1970 enabled the Arab oil embargo of 1973, and OPEC’s increase in posted oil price in 1974, to raise oil prices to such a degree as to cause a significant decrease in global oil consumption.

- Efficiency and environmental controls enacted for the first time: The Clean Air Act (1970) and Clean Water Act (1972) were substantially increased in scope and enforcement. The environmental and energy changes encouraged significant investment in utilities (e.g., wastewater treatment) and resource extraction along with a focus on consumer energy efficiency for the first time since industrialization.

Structural Shift 2 (2002):

One of the theories of ecologists (e.g., Howard T. Odum and Robert Ulanowicz) is that systems must have some “structural reserves” in existence to be able to respond to resource constraints or other disturbances that might occur in the future.

The major change that occurred in 2002 was that energy and food no longer continued to get cheaper. If you’ve followed my work, you know this already (see my blog from 2012)!!! As I’ve stated in even more detail in my papers in 2015 (Part 2 and Part 3 of 3-part series in Energies) this is the defining macro trend of the Industrial Era (no, really …).

In response to this second structural shift from energy and food costs, it is clear that the U.S. economy did trade off structural reserves for efficiency. Efficiency is the opposite of redundancy in Figure 1, so that the efficiency of the economy decreased all the way to 2002 after which it started increasing efficiency. The U.S. economy decreased structural redundancy and equality for structural efficiency (e.g., increasing metrics of efficiency and hierarchy) after food and energy expenditures increased post-2002.

So after 2002, the U.S. economy (and by my inference, the same thing is happening in each world economy overall) had to shift money into FEWER sectors and FEWER types of transactions.

- China had entered the World Trade Organization in 2001 and started to become the world’s manufacturer. This decreased monetary flows to domestic manufacturing.

- Financial deregulation in the 1990s, including the Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act of 1999 which repealed the Glass-Steagall Act, increased the monetary flows to the financial sectors.

- These two effects (China and financial deregulation) led to increased demand and speculation for energy and commodities, so that monetary flows increased to the oil and gas sector (remember the highest oil price of $147/BBL in July of 2008 during the height of the Great Recession) to meet U.S. and global demand.

APPENDIX: How to interpret the results in Figure 1 via the methods of the paper.

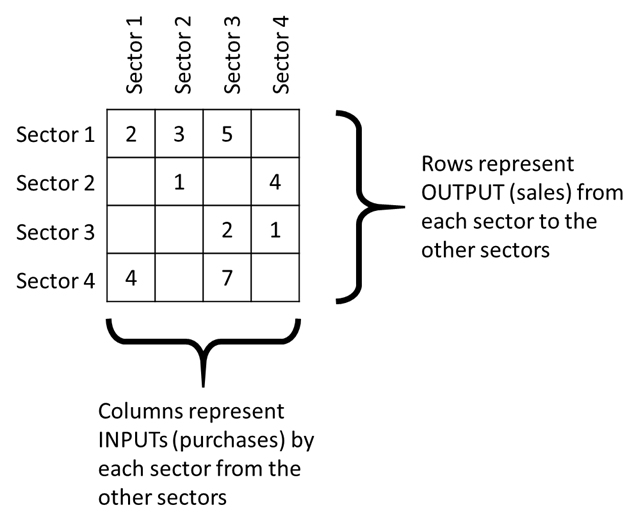

- Consider the U.S. economy as many ‘sectors’ buying and selling products with each other (See Figure 2)

- – Example sectors are “oil and gas sector” and “farming”, etc.

- Each sector also produces some “net output” (a column “to the right” not shown in FIgure 2)

- – This net output from each sector sums to GDP

- – Also represents largely what you and I buy as consumers

FIgure 2. The economy’s transactions are often viewed via the “input-output” table where each entry represents how much of a given sector (on the column) purchases from a given sector (on the row).

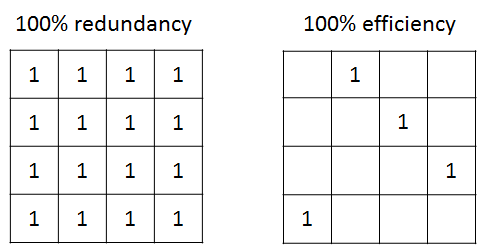

- A highly redundant economy (or system or network of flows) interacts with many of the possible partners in many ways and relatively equally (Figure 3 – LEFT). This might not be the best for growth, but you have “backups” in case things go wrong with one of your partners.

- A highly efficient economy (or system or network of flows) interacts with fewer possible partners such that there are fewer sectors or people to deal with to get things done (Figure 3 – RIGHT). This efficiency can, and typically does lead to increased potential for growth.

Figure 3. What the distribution of monetary flows (from one sector to another) looks like for an economy (or generically a network of flows) that is fully, or 100%, redundant (LEFT image) and one that is fully, or 100%, efficient (RIGHT image). The numbers don’t have to be all “1”, they could be any number that is the same.

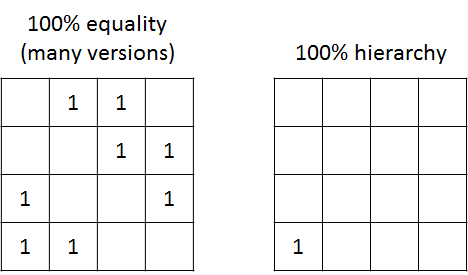

- A highly equal economy (or system or network of flows) interacts with many of the possible partners in equal manners such that every sector or actors sells and buys the same total amount of goods and services (Figure 4 – LEFT). Note that both the images in Figure 3 are also 100% equal. This is not a practical expectation because we can easily understand structural relationships among economic sectors that will prevent equality (e.g., the “oil and gas extraction” sector sells most of its products to the “refined oil products” sector).

- A highly hierarchical economy (or system or network of flows) has a small number of sectors that dominate the transactions and monetary flows (Figure 4 – RIGHT). In the extreme case of FIgure 4 – RIGHT, there is only one type of transaction that occurs (Sector 1 purchasing stuff from Sector 4) and the economy actually no longer is defined the same (e.g., Sectors 2 and 3 don’t effectively exist since they have no transactions).

Figure 4. What the distribution of monetary flows (from one sector to another) looks like for an economy (or generically a network of flows) that is fully, or 100%, equal (LEFT image) and one that is fully, or 100%, hierarchical (RIGHT image). The numbers don’t have to be all “1”, they could be any number that is the same.